Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: January 24, 2012

I have an entire shelf overflowing with Civil War histories. Almost all are devoted to specific battles and campaigns, specific armies, subjects, or central figures. Most deal tangentially with Washington, D.C., during the war—and most of this is in reference to Lincoln. Digested in parts over time, these descriptions had—I felt—provided me a decent understanding of the city, its character, its day-to-day existence from 1861-1865. But then, through an InHeritage documentary project, I was introduced to “Reveille in Washington” by Margaret Leech. I quickly realized my understanding was anecdotal, not linear or anything near complete. Like most Civil War buffs, my historical perspective was from out-in-the-fields looking back at D.C. Leech flips this view entirely. You view the era through the lens of Washingtonians, a city on the border of North & South (some would argue more South, than North) with strong camps supporting either side. Leech’s storytelling narrative provides the reader a view from the inside looking out. It is a ‘looking at something you have seen a thousand times, in a new light’ moment.

I have an entire shelf overflowing with Civil War histories. Almost all are devoted to specific battles and campaigns, specific armies, subjects, or central figures. Most deal tangentially with Washington, D.C., during the war—and most of this is in reference to Lincoln. Digested in parts over time, these descriptions had—I felt—provided me a decent understanding of the city, its character, its day-to-day existence from 1861-1865. But then, through an InHeritage documentary project, I was introduced to “Reveille in Washington” by Margaret Leech. I quickly realized my understanding was anecdotal, not linear or anything near complete. Like most Civil War buffs, my historical perspective was from out-in-the-fields looking back at D.C. Leech flips this view entirely. You view the era through the lens of Washingtonians, a city on the border of North & South (some would argue more South, than North) with strong camps supporting either side. Leech’s storytelling narrative provides the reader a view from the inside looking out. It is a ‘looking at something you have seen a thousand times, in a new light’ moment.

I must also drop kudos to Leech who, though a member of the distinguished post WWI literary club, The Algonquin Roundtable, researched, wrote and published this solid work of history during an era when history depts. and publishing in general seemed like an all-male fraternity. As if that gender-busting achievement was not enough, this book won a Pulitzer in 1942. It is a rare blend of literary-readability wrapped around groundbreaking research. And though time and discovery have given us a much broader understanding of not just the facts but their long-term impact since this book was published, it stands the test-of-time. In part, this is due to Leech recognizing the emerging current of that era, which sought to tell the truth about the war: that it was no simple political argument over rights & honor, but a comprehensive reinterpretation on how America would move, as a nation, into the future. Published during another cataclysmic war, this story shows Washington as the central city in the war itself. Everything was on a pivot around it. And like the war itself, Leech shows the transformation of D.C. in parallel with the soldiers who fought and the civilians that supported the effort: from the green, exuberant and nervous, to the hardened, fatalistic, yet resolved. With that in mind, here are a few great quotes from the hundreds marked ‘in the margins’:

-

With hostilities opening in early April 1861, many believed Washington could fall quickly to a Rebel force; Union volunteers finally arrived to shore up the defense of the ‘National’ capital … “For six days at the very outset of hostilities, it had shivered at its fate—a border town, divided within itself, and nakedly exposed to danger in a time of great rebellion.”

-

Disastrous defeats were plentiful for the U.S. Army of the Potomac early in the war; but the defeat at Second Mannasas in August 1862, was devastating to morale. Leech captures the mood of the beaten now-veteran Union soldiers falling back on their capital … “They flooded back in disorder on the Alexandria road, flopped down to rest, indifferent to the tumult of the retreating infantry and cavalry, artillery and wagons. Their great fires illuminated the whole countryside. Across the bridges, they crowded into the capital, congregated in low groggeries and staggered drunken and loud-mouthed in droves on every street.”

-

Here is a fascinating instance in which New York troops harbored African Americans who had run off from Virginia into the Union lines around D.C. Until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the U.S. government was still bound by law (Dred Scott) to return ‘runaways’ to a slaveholder if they could show proof and a warrant was issued. But as we see the order was not always met with compliance … “Next morning, when a deputy marshal went down to get them, with his warrants and an order from the provost marshal, he was admonished by officers and soldiers that they would see him in hell before they gave the Negroes up.”

-

A great telling of the official White House event welcoming U.S. Grant, who took over command of U.S. forces in early 1864 … “Wild cheers shook the crystal chandeliers, as ladies and gentlemen rushed on him from all sides. Laces were torn, and crinolines mashed. Fearful of injury or maddened by excitement, people scrambled on chairs and tables. At last, General Grant was forced to mount a crimson sofa.”

-

As well as the seat-of-gov’t, Washington was transformed into a mass hospital with buildings re-purposed and makeshift structures built up all over the city. Here is a tragic, common scene following the start of the brutal bloody spring campaign of 1864 … “There were three days and nights in which the procession of ambulances never ceased.”

-

New Year’s Day, 1865 … “With high heart, the New Year’s Eve merrymakers went singing, “When This Cruel War Is Over.” The New Year’s reception at the White House—held on Monday, January 2—was a surging crush of people.”

-

Lincoln’s funeral day … “The columns of the White House were shrouded and somber folds were looped on the Federal buildings, and on residences and places of business in all parts of town. Sorrow seemed universal amongst the poor. Hovels and huts had their scraps of black cloth or ribbon. On the Avenue before the White House, hundreds of colored people stood wailing in the rain.”

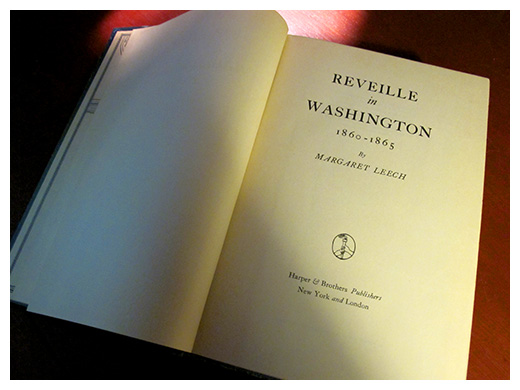

SOURCE : Leech, Margaret. Reveille in Washington. New York: Harpers & Brothers, 1941.