Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: v.2 2015-2016 (v.1 2003)

I have toured the tragic land that makes up the National Military Park @ Fredericksburg, Virginia, several times since my first visit in 2003. But it was the experience of the tour I took in April of that year through which I have filtered each return trip and this written narrative. That tour was of a string of “Civil War Rambles” that had become a yearly Christmas gift to my Dad. We would go on to Charleston and Chattanooga, Vicksburg and Gettysburg. We would follow Sherman’s March on Atlanta and to the Sea, as well as retracing the final days of the Army of Northern Virginia across southern Virginia via “Lee’s Retreat.” But of them all, there was something about that 2003 tour of Fredericksburg that stood out. For all of the grotesque human destruction that defines our Civil War and the shadowed lands where it took place, the ever present and electric sense of tragedy seems more pronounced, more present @ Fredericksburg.

One › Onto Fredericksburg

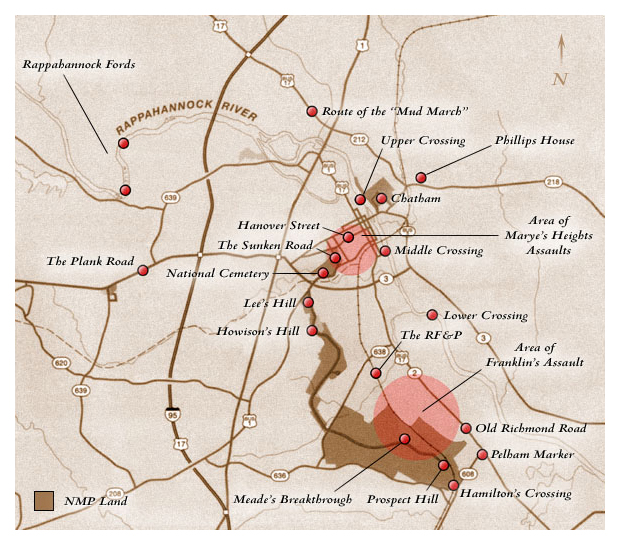

Making your way down through east Virginia takes you through a region saturated in Civil War heritage like nowhere else. Historical markers are every few miles, the past never far away. The final stretch into Fredericksburg from the north, itself, runs down State Route 17, the modern trace of road along which Ambrose Burnside would commit his final blunder as commander of the Union’s Army of the Potomac: a ignominious winter slog aimed to get beyond the flank of the Confederate army then in winter quarters that devolved instead into an embarrassing mess from then on harangued as “the Mud March.” And yet, despite history being etched into the bones of this land, the present and future move through it relentlessly.

To anyone who does any amount of touring Civil War sites and fields, the threat commercial and residential development poses is often obvious. But in few places is it more obvious than on Williams Street running west from Fredericksburg into central Virginia as Route 3. In the 1860s this was the “Plank Road,” one of the few improved roads in the area. Such roads and turnpikes always figured prominently in the mass shuttling of troops to, from and during campaigns. From late November 1862 through May 1863, the Plank Road proved an arterial route for Robert E. Lee’s C.S. Army of Northern Virginia. Down it, the Confederates marched into impregnable positions on the hills west of Fredericksburg, doubling-back the following spring to repel a daring Union thrust pushing east from the Chancellor House. Today it is many solid miles of commercial indigestion: a built-over run of chain-stores, strip malls, winding service-roads, intersections and parking lots gobbling up all rural scenes in the worst car-centric way. It seems like it would surely overwhelm the historic downtown still nestled comfortably into a bend of the Rappahannock River; what was a rural if well-used route but a generation ago, now a six-lane serpent pouring into central Virginia. So, it comes as a relief to discover that this mostly fades away on entering “old” Fredericksburg, the town’s historic character intact.

Fredericksburg can rightfully claim itself one of the more historic towns in America. With roots in the early 18th century, it boasts of colonial and Revolution-era heritage in the names of Hugh Mercer, James Monroe, the general himself, George Washington, and his mother Mary. But it is the town’s more infamous role that sets the mood: the December 1862, Battle of Fredericksburg—at once a tragic disaster and one of the most complete victories of the Civil War.

* * *

On the night of November 7, 1862, the precise, plodding and irrefutably vain, George McClellan, was relieved as commander of The U.S. Army of the Potomac. Command of the Union’s flagship army fell to a reluctant Ambrose Burnside, who felt himself unfit for the role. He went on to accept the honor, nonetheless, if only to deny his rival, Joe Hooker, who would be awarded the post if he refused. This change in command came at a critical point. The Army of the Potomac had won a tactical, if not complete victory at the gruesome Battle of Antietam that September, having repelled the first Confederate invasion of Maryland (though the South would always claim Maryland its own). Antietam would provide the political leverage enough for President Lincoln to issue his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which he did that fall. This action alone raised the moral cause of Union above the simple sectional, political and economic fractures on which many claimed the war was being prosecuted, in turn creating a diplomatic dilemma for the foreign powers of England and France should they attempt to intervene on behalf of the South—a longed-for hope of C.S. leaders throughout the war.

But any momentum that the Union victory at Antietam had yielded fast melted away. McClellan allowed Lee to retreat to safety up the Shenandoah Valley and had been slow to pursue. Coupled with past instances of “the slows” (Lincoln’s own sarcasm) and more than one instance of outright insubordination, McClellan’s tenure as chief was terminated. Burnside was given little time to get settled before he himself was pressed by leaders in Washington on his “intentions.” But he met the challenge: In less than a week, he had drafted, submitted, revised, then re-submitted a plan that was finally approved. He would race the six corps now under his command—118,000 men having been organized into three “Grand Divisions” of two corps each—around the flank of Lee’s then scattered forces, throw pontoons across the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and, keeping close on the Richmond Fredericksburg & Potomac railroad for use as a supply line, light out for Richmond. He would induce Lee to attack him on his terms.

* * *

I have only ever had single days to tour Fredericksburg. So, being hampered by the “slows” was never an option. Preparation must carry the day. And for over 20 years now, I have relied heavily on my highlighted, scribbled-upon, earmarked and otherwise battered and abused Time-Life “Civil War” series volumes as easy-to-use in-the-field resources. The volume: Rebels Resurgent has accompanied me to Fredericksburg every time I have been, as have the moving, lyrical accounts within Bruce Catton’s, Glory Road, and the second volume of Shelby Foote’s masterful trilogy. In 2003, we even employed a useful stop-by-stop tour narration on CD and, of course, the standard NMP maps and literature. But the definitive account of the battle by historian, Frank O’Reilly—The Fredericksburg Campaign—now serves as my core deep-dive foundation for understanding and interpreting this cataclysmic fight.

Armed with heavy-calibre history in hand and in mind, I synchronize Civil War tours where possible with the flow of events. Down off of Route 3 and into town, you move beyond the sprawl further west. It all seems difficult to reconcile: A modern run of ubiquitous commercial malls, strips, corridors that could be anywhere America dominating a landscape so near to where thousands suffered and died, desperately. But thankfully, that all disappears in the rear-view as you move down Williams Street heading for the park’s HQ: the colonial-era mansion known as “Chatham,” itself HQ for the “Right Grand Division” during the debacle to come.

* * *

By late 1862, Robert E. Lee had already cemented a reputation for being decisive, if not outright daring. With the odds always long, he and his Confederate command often had little choice. But on the morning of November 15, 1862, both the opportunity for decisive action and even more so the odds were with his newly installed counterpart, Ambrose Burnside. Following the retreat from Maryland, Lee had positioned his I Corps under James Longstreet at Culpeper in north-central Virginia, allowing Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s II Corps to remain masked by the mountain ranges of the Shenandoah to the west. Ideally, this subterfuge could be leveraged to strike the initially languid pursuit of the Union army into Virginia. But it was Burnside who would take the initiative, staging a deceptive feint against Longstreet on the morning of the 15th while he set the vast bulk of his army on the road to Fredericksburg.

The three U.S. “Grand Divisions”—the Right under Edwin Sumner, the Center under Joseph Hooker, the Left under William Franklin—marched out in that order over the next two days. Sumner’s men covered the forty miles to within sight of Fredericksburg in two grueling days, Hooker’s and Franklin’s men closing up soon after. Burnside had reached his objective before the enemy; but it would not matter an ounce if he could not put his army across the river into town and secure the RF&P. The army had far outpaced the pontoon trains that’d been ordered to meet the army. This would prove a huge logistical error. The pontoons were a necessity, all other bridges across the Rappahannock, including the railroad trestle, having been destroyed earlier in the war. And as the Union army waited for the engineers to arrive, a driving three-day rainstorm poured down, swelling the river and scotching any possibility of backtracking and fording the army further upriver. Burnside was at the mercy of a U.S. Quartermaster Dept., who was right then afflicted with its own version of the “slows.” Half of the pontoon bridging material the army would need had been sent overland via wagon train, the other half having been ferried down the Potomac. Yet both deliveries did not even leave Washington D.C. (fifty miles north) until November 19, the day Sumner’s men pulled up into Falmouth directly across the river from Fredericksburg. The rainstorm mired the overland train in mud over its axles. It was quickly ordered back to D.C. to be ferried down the Potomac, as well. The delay unraveled Burnside’s entire plan. The pontoons did not arrive at Aquia (a Potomac river town about ten miles to the north of Fredericksburg ) until November 25. This alone provided Lee with more than enough time to pull together his lean army and intercept the Union’s aborted drive on Richmond. Burnside had lost the race. A follow-up plan of improvising a new crossing miles south at a riverbend called “Skinker’s Neck” was thwarted by the timely arrival of Jackson’s hard-marching corps from the Shenandoah. The Army of the Potomac, from general to private, could only brood over the opportunity missed, as they watched and listened to The Army of Northern Virginia confidently perfect one of the strongest defensive positions of the entire war. Colonel Samuel Zook, a U.S. II Corps brigade commander whose men would absorb the horrific price of storming those defenses, penned an acrid letter prior to battle, predicting: “I expect we will be licked, for we have allowed the rebs nearly four weeks to erect batteries &c. to slaughter us by thousands in consequence of the infernal inefficiency of the Quarter Master Genl & his subordinates.”1

The core of both these armies were veterans by late 1862. Given the unforeseen sacrifice and bloodshed that the war—still four months from its halfway point—had already produced, prophetic fatalism was certainly their right. As the mountains of letters and reminiscences that these men left behind can attest, they called it as they saw it. And who could blame them? It was quite possible to be dead the following day.

NEXT: Two › The Crossings & The Prelude